|

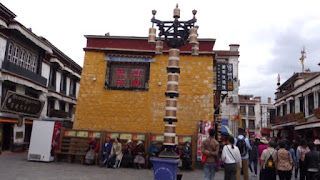

| Photo: Wikimedia |

“What can I talk with Samuel, this absurdist writer?” that

was my reaction to stenote, the publisher, when he first asked me to interview

Samuel. “He wrote this book titled ‘Texts for Nothing’, what can one expect to

discuss about nothing? He even wrote this in the book ‘He thinks words fail

him, he thinks because words fail him he's on his way to my speechlessness, to

being speechless with my speechlessness, he would like it to be my fault that

words fail him, of course words fail him’. What can we talk with such words,

they are so obscure. I heard from Charles Juliet that he is quite capable of

meeting somebody and sitting for two hours without uttering a word.”

My publisher said: ”No, not really, he is not such a

reclusive person, he likes to drink quite heavily, hopping with friends from

one bar to another, enjoys chatting about cricket, actually he played cricket

for Dublin University, and he had won medals for swimming and boxing. He also

played golf and tennis. So, to start the conversation with him, try bringing a

bottle of wine and talk about sport.”

Encouraged by my publisher, I flew to Paris and made

appointment with Samuel to meet at Îles Marquises restaurant in Monparnasse. I

brought with me a bottle of Lacrima Christi which he took delightedly. But, his

tall, gaunt and archaic presence made him seemed aloof from the cozy

surrounding.

I started:

“Sam, who is your favourite cricket player?”

Samuel glowed with pleasure and responded:

“Frank Woolley, I had admired as a boy. You know, I saw him in the bar at Lord's cricket ground. He was escorting the legendary 84-year-old Wilfred Rhodes, perhaps the greatest England cricketer ever. By that time, Rhodes was totally blind.”

Then he stared and pointed out on the wall above our table photographs of the great boxers: Joe Louis,Georges Carpentier and Jack Dempsey.

I said:

“My first thought, sport seems out of place in your world. Your characters emerge as homeless people, down-and-outs, tramps, failures, and you wrote ‘Fail again, fail better’ in your ‘Worstward Ho’ story.”

Samuel:

“Actually, I wrote ‘All of old. Nothing else ever. Ever tried. Ever failed. No matter. Try

again. Fail again. Fail better.”

I said:

“ You achieved your own gold in 1969 for Nobel Prize in Literature. How

did you feel?”

Samuel:

“My publisher, told me in a telegram ‘Dear Sam and Suzanne. In spite of

everything, they have given you the Nobel Prize. I advise you to go into

hiding.’ We anticipated a spike in publicity and people trying to reach them.”

“You were right, the Swedish Television asked for an interview”.

Samuel:

“I agreed only with the stipulation that the interviewer couldn’t ask

any questions. “

I said:

“Thus you created a bizarre ‘mute’ interview and sent the video clip to

them showing yourself in silent in nature, with background of the sound of wave

from the beach, and the sound of bird chirping. And you didn’t attend the

award, you sent your publisher to take the award, while you and your wife

Suzanne travelled to Tunisia to avoid publicity.”

Samuel, citing the opening of Texts for Nothing 4:

“Where would I go, if I could go, who would I be, if I could be, what

would I say, if I had a voice, who says this, saying it's me?”

I said:

“When your play ‘Waiting for Godot’ premiered at Théâtre de Babylone in

Paris, it is reported that many audience members walked out of the theater,

perhaps because of the unconventional form of the show, there is no plot, the

characters are not revealed, the dialogues are random and ridiculous. Two

tramps, Vladimir and Estragon, are waiting to meet someone named Godot, who

eventually does not turn up. But some of the critics liked it, some critics

said that pointlessness is its very point in this kind of theatre.

Martin Esslin called it The Theatre of the Absurd, in his book with

same title, depicting ‘sense of metaphysical anguish at the absurdity of the

human condition’. And this type of theatre has been associated with your name.”

Samuel:

“The early success of Waiting for Godot was based on a fundamental

misunderstanding, that critics and public alike insisted on interpreting in

allegorical or symbolic terms a play which was striving all the time to avoid

definition.”

I said:

“The greater part of Waiting for Godot's success came down to the fact

that it was open to a variety of readings and that this was not necessarily a

bad thing.”

Samuel:

“Why people have to complicate a thing so simple I can't make out. It's

all symbiosis; it's symbiosis”.

I said:

“Then, may I ask you who or what is Godot?”

Samuel:

“I don't know who Godot is. I don't even know, above all don't know, if

he exists. And I don't know if they believe in him or not – those two who are

waiting for him.”

I said:

“Godot’s messenger boy tells Vladimir that Mr.Godot has sheep and

goats, and the boy tends the goat is not beaten by Godot, while the boy’s

brother who tends the sheep is beaten by Godot. This seems to be the reversal

of the Bible story in which Christ separates the sheep, representing people who

will be saved, from the goats, representing people who will be damned.

In the play Vladimir asks if Estragon has ever read the Bible. Estragon says all he remembers are some colored maps of the holy land. Vladimir tells Estragon about the two thieves crucified along with Jesus. One of the gospels says that one of the thieves was saved, but Vladimir wonders if this is true.”

Samuel:

“St Augustine’s reflection on this story is ‘Do not despair, one of the

thieves was saved: do not presume, one of the thieves was damned.”

I said:

“I reckoned that perhaps the theme of the story is the two who are

waiting for Godot, rather than Godot.”

Samuel:

“An inmate of Lüttringhausen Prison near Remscheid in Germany, stage the play in German and after that wrote to me: ’You will be surprised to be receiving a letter about your play Waiting for Godot, from a prison where so many thieves, forgers, toughs, homos, crazy men and killers spend this bitch of a life waiting ... and waiting ... and waiting. Waiting for what? Godot? Perhaps.”

I said:

“During the World War II in 1941 you and Suzanne joined the French

resistance unit Gloria SMH, an information network, but in 1942 the group was

betrayed by a double agent, members of your group had been arrested by the

Gestapo. You had to flee Paris, heading for the Unoccupied Zone in the south of

France. It took almost six weeks, sometimes alone, sometimes with other

refugees, to cross into the free zone at Chalon-sur-Saône in Burgundy; you made

your way by hiding in barns and sheds and sometimes behind trees, inside

haystacks and down in ditches.”

Samuel:

“I can remember waiting in a barn, there were ten of us, until it got

dark, then being led by a passeur over streams; we could see a German sentinel

in the moonlight. Then I remember passing a French post on the other side of

the line. The Germans were on the road so we went across fields. Some of the

girls were taken over in the boot of a car.”

I said:

“You also witnessed the aftermath of bombing of St-Lô in 1944. The town

located in Normandy bombed by the American, as it served as a strategic

crossroads. It caused heavy damage, most of the city was destroyed, and a high

number of casualties, which you reported as ‘The Capital of Ruins’, you

witnessed real devastation and misery, people in desperate need of food and

clothing, yet clinging desperately to life.”

Samuel:

“St.-Lô is just a heap of rubble, la Capitale des Ruines as they call

it in France. Of 2600 buildings 2000 completely wiped out. . . . It all

happened in the night of the 5th to 6th June. It has been raining hard for the

last few days and the place is a sea of mud. What it will be like in winter is

hard to imagine.”

I said:

“After the War, a lengthy clean-up began, literally by hand including

the corpses of residents and soldiers, which lasted about six months. However,

officials hesitated to rebuild Saint-Lô, some were willing to leave the ruins

as a testament to the martyrdom of the city. The population declined,

preferring to reinhabit its city. You volunteered to join the Irish Red Cross

to build a provisional hospital in this town”

Samuel:

“The new hospital was designed to be provisional. But ‘provisional’, is

not the term it was, in this universe become provisional.”

THE END

Sources: